What is Home?: Boundaries of our Inner and Outer World

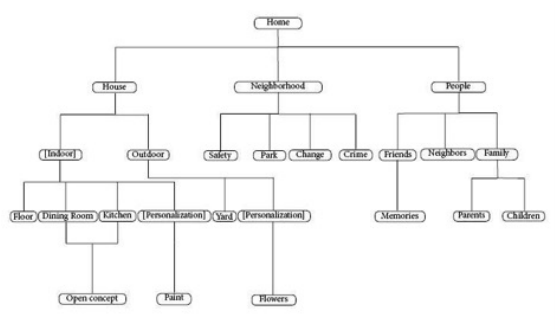

Rough taxonomy from my research of “home”.

Rough taxonomy from my research of “home”.

Bella Biwer, Undergraduate student, Architecture

Home is a number of things, and it takes on a different range of meanings with each individual. Mary Douglas says that home “is the realization of ideas” [1]. She also claims that home can either enrich the personality, or cripple and stifle it [2]. To each person, home has a different definition that can be analyzed in the context of the dwelling of the individual. A house is a type of space, but a home is a place, which is much more complex. Most often, the home is a domain of private space for the resident, and some boundary exists dividing the private space of the resident from the outer or public space. The outer world or domain is where social interactions with outsiders is made, whereas the inner domain is more intimate. All people have some type of such boundary. My analysis will focus on the construction of divides between the “inner world” of the resident and the “outer world” of the public. I will also discuss what home means to several residents of the Washington Park Neighborhood in Milwaukee through the use of ethnographic techniques.

When speaking of such domains and boundaries, a general understanding of culture is necessary. Culture is a complex idea that is not capable of being physically grasped. However, through primary sources such as oral histories, it is possible to understand the complexities of a specific culture. Some of the essential concepts are beliefs, expectations, social norms, and environment. Beliefs can refer to everything from religion to science and in between. Expectations and social norms can be interchangeable terms. They are the set rules that are established over a long period of time and are shaped by both beliefs and environment. Environment both encloses and shapes the other aspects of culture in terms of movement and procedure.

A cultural scene, like the one I have analyzed, is a physical area with some type of boundary that separates it from the surrounding environment or culture. Such a boundary can be a geographic feature like a body of water, or a man-made feature. A cultural scene will almost always possess cultural traits that vary from the cultural scenes around it. In order to understand culture, ethnographic techniques may be used. Ethnography directly relates to culture, as it is the dissection and analysis of it. Whether it be that of a high school bathroom or a library book club, conclusions can be drawn about the what, how, and why of that culture by using ethnographic analysis. I will begin by covering the Field Work Methodology that I utilized. I will then cover the social and physical characteristics of the Washington Park neighborhood. I will finish by analyzing the divide between the inner and outer worlds that many of the informants refer to as well as the culture of “home” in the context of the oral histories conducted by the BLC Field School.

Field Work Methods

The specific cultural scene of Washington Park was chosen by Professor Arijit Sen and the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School because of its unique economic and social conditions, which will be discussed later. Contact with the 22 informants was made through Arijit Sen and the BLC Field School and connections with the staff of ACTS Housing, who gave the Field School access to their clients and some staff. ACTS Housing is an organization rooted in the Washington Park neighborhood whose goal is to improve the social and physical aspects of the community through providing opportunities for homeownership. The organization also gave the Field School access to foreclosed homes that were going to be cleared by the city. Most of the informants are affiliated with ACTS, however some of them are tenants. Two of the interviews that I analyzed and will be discussing later were with tenants. Contact was made with these individuals through their landlord. An issue that we faced was that tenants were very underrepresented in our research. For this reason, the Field School could not make any generalizations about how tenants view home. This is significant because tenants perceive home differently than homeowners (i.e. differences in investment). However, their homes still hold meaning.

Of the 7 interviews that I analyzed, the informants’ ethnicities were African American and Hmong. All of the informants have faced substantial conflict in their lives, everything from immigrating from Thailand to being diagnosed with cancer. However, they were all very proud of their homes and how they have overcome these struggles. I was not involved in this process of informant selection, but began the semantic analysis afterwards. I was also not involved in the interview process. The interviews with the informants were conducted by 12 members of the BLC Field School[3]. This task was completed before I arrived, and I inherited the information for the purpose of my research.

My initial research was focused on the idea of home and what it meant to the informants. I began by listening to most of the 22 interviews that were conducted by the BLC Field School (more than the 7 I settled on). I took notes on which words the informants used most often to describe home. This step helped me to become more familiar with the taxonomy process and know what terms to look for. With the help of my professor, Arijit Sen, I narrowed the selection of interviews down to 7 that seemed to represent the Washington Park neighborhood the best. I then listened to these 7 interviews again and made rough, very specific taxonomies as I went. Once the rough taxonomies were made, I constructed digital, more narrow taxonomies using the rough copies I had made. With these digital copies, I was able to more clearly observe the similarities between the categories informants used. At this point, I could then identify the most common terms and create an overall taxonomy.

Once this research was completed, I began looking into the boundaries that residents create between their inner/private space and the outer areas in which socializing may occur. For this portion, I focused on the information provided by 4 of the 7 interviews that I had previously focused on. This boundary varies with each informant, but are always physical features that somehow divide or designate different types of space. The range of such a boundary may be contained completely in the structure of the home or extend to the exterior of the home and the community. The interests and social statuses of the informants that I focused on define where the boundaries are placed.

The Setting

The physical setting of Washington Park is western and northwestern Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Brookfield and Wauwatosa border this area to the west. The area is mainly residential, yet some establishments such as churches, restaurants, stores, and gas stations are present. The racial profile of the town is largely African American. There is also a large number of Hmong immigrants from Thailand that distinguish Washington Park from the rest of Milwaukee. Foreclosure, low homeownership, crime, and low income are prevalent issues in the area. My analysis will focus on the construction of divides between the “inner world” of the resident and the “outer world” where public engagement occurs. These two worlds will constitute as the major domains of the informants’ cultural scenes.

The Cultural Description

The domains I will be evaluating are inner and outer spaces distinguished by resident-constructed boundaries. I will later analyze the definition of “home” in general in the Washington Park Neighborhood. These ideas go hand in hand because of the nature of a home, for either public or private use or both. I will focus on the inner and outer domains in the context of 5 oral histories and 4 types of boundaries. These 5 informants reference the boundaries between the two domains most frequently out of the interviews that I analyzed.

Angela Pruitt: Angela Pruitt places her divide between her inner world and outer world at the outer walls of her house. The interior of her house is her own domain where she can do personal business or activities. However, she spends the majority of her time outside. Her yard, garden, and the rest of the neighborhood are her outer world. While her yard and garden are her property, she views them as community space that should be used for resource. During the interview, Pruitt mentions playing all day as a child, and then grabbing fruit and vegetables from neighbors’ yards when she got hungry. This is what she wants for the community.

Pruitt’s vision for the community is for there to be space where people can come together to communicate and strengthen relationships in the neighborhood. This goal corresponds with her desire for there to be as much space for interaction as possible, including her own property. She wants people to use the garden in her yard and the growing orchard across the street for their own benefit as long as they are respectful: “This is an orchard, we’re trying to grow fruit for the community. If we knock them [trees] down before they start to grow we won’t have anything.” Pruitt’s use of we and community in this statement show that her work is for others, not just herself.[4]

Charmion Herron: Charmion Herron places her boundary at the border of her property and lawn. Since her mother died, her home has become a sort of memorial to her mother’s memory. She makes sure to keep and preserve all of the features and items of the house just as her mother would have wanted it. Some of these features are outside the walls of the home. Herron refers to the home’s staircase often because her mother loved it: “My favorite [place] though I will say are the stairs… I know she loved the stairs.” For this reason, the staircase is her favorite feature of the home. However, she also mentions outdoor features such as her mother’s rosebush and geese planters in connection to the staircase: “The rose bush, she loved her rose bush. I have the geese outside the front porch that I keep… They all broken up and torn up but I keep ‘em because she for some reason every house she wanted her geese.” This suggests that Herron’s private, inner world also consists of the exterior of her home because of the connection she has created between the home and her mother’s memory. For Herron, her home is a type of safe haven. Her outer domain consists of everything outside her yard. She often refers to the block positively because of the memories she has growing up there and playing outside. She feels more safe on her block than in the rest of the neighborhood. Herron mentions crime in the neighborhood, for example at the McDonald’s nearby, but never refers to engagement in the community in the outer domain.[5]

Lanard Robinson and Leroy Washington: Lanard Robinson and Leroy Washington differ from the other informants being evaluated because they are tenants. They also live together in a home with one other friend and their families. The boundary they have created to divide their inner and outer worlds is the exterior walls of their building. Their home is where socialization and interaction with close friends and family occurs. During the interview, they often refer to the home as a family. They refer to the building as a safe place where their kids can play and where they can socialize with each other. Washington says during the interview, “I’ve made some friends… new family here. I’ve got three extra brothers… This my family, my friends… That’s what makes it home for me.” Robinson goes on to mention, “It’s one big family the whole building. My kids go up and down [the stairs]… they feel free to go over here…. It’s almost like a family.” The outer domain, on the other hand, consists mainly of places to eat, the park, and convenience stores:

Robinson: We have a lot of fast food restaurants around here… this neighborhood itself… my oldest [child]… grew up back in Milwaukee here... This neighborhood reminds me of all my kids when they were little, taking them to the park and having picnics. Now I’m doing the same thing 20 years later with my grandkids.” Interaction with people beyond their inner circle is rare, but when it does occur it is at these designated areas. Outside social interaction isn’t common for Robinson in Washington at other places in the community.[6]

Pastor Wang Chao Lee: The layout that Pastor Wang Chao Lee has chosen for his home reflects his position in the church and community, as he requires both public and private space. The open lower level serves as a public space, and the upper level serves as private space. The L-shaped staircase which is parallel to the front door serves as a barricade between the two aspects of his life. For example, his outer domain, the lower level, may be used for church meetings or consultations, whereas the inner domain, the upper level is solely for family use. His upper level is closed off, physically and hypothetically, to the public. It is a space that Lee and his family can use for more intimate interactions amongst the family. Lee does not refer to the outside of his home besides the church. This connection between the physical church and church meetings, which sometimes occur on his lower level, suggest that he considers the lower level of his home to be part of the “outer” domain. During his interview, Lee references how he intentionally created this divide: “The staircase… [is a] major redesign to my taste… And downstairs with more guests coming next to the kitchen… we want to host more guests…”, “ Larger bathroom, with kids… and the upper 3 bedrooms… knowing that the family will use it [bathroom] more.” This is a major example of how Lee has divided his home into the two domains.[7]

I found that the terms house, neighborhood, and people were used in every oral history in reference to home. Different people experience the same place in different ways due to varying contexts[8], and while the experiences and interpretations of the people were different, these common terms were always present. Common terms in reference to the physical structure of a house included cosmetic features, both indoor and outdoor. For example, kitchen, dining room, floors, paint, open concept, and yard were frequently mentioned. In reference to neighborhood, terms such as safety, crime, park, and change were common. When speaking of people, family, friends, and neighbors were also recurrent terms. All of these terms can be put into context depending on the informant.

Conclusion

The divide between private, non-social space and social space is an important aspect of home and community. All people need a place for public social interaction, but also a place to have to only themselves. Without this divide, there would be no rationality or expectations of how to behave in certain spaces. While this boundary is different for each person, the types of activities that occur in each domain have commonalities. Inner or private spaces, I found, are most often where people spend time with their families and close friends. Most often a more closed off and quiet space, it may be used for intimate conversations and interactions or time for one’s self. Outer space, however, is where interaction and engagement with acquaintances and the community is expected to occur. This may be in individual, defined places in the neighborhood or a more general area consisting of everything outside of the house or yard.

From the information provided by the informants, I can interpret that the Washington Park neighborhood has faced much social turmoil in the past, but is now improving through the work of many dedicated residents of the community. Many of the residents are concerned about crime and foreclosure in their neighborhood. They are optimistic, however, about the resources that are being put in place in order to minimize and potentially eliminate these issues. The focus of the residents is primarily on relationships with friends, family, and neighbors. Most believe that this bond is what will help lift the neighborhood out of its decades-long slump. Residents enjoy events like block parties, family get-togethers, and going to the park, after which the neighborhood is rightfully named. The park is certainly the centerpiece of the cultural scene.

Future research can be done evaluating the meaning of home in the context of the space and how it influences how residents act, think, and participate in daily activities. Everything from the structure of a building, interior and exterior, to its ambiance can impact how we think. For example, the factors of our physical environment may influence how we behave, how we understand others, and how we create who we are. The Spacial Performance theory states that we, as humans, create places, but those places make and shape us. With this knowledge, it would be interesting to assess if there is a correlation between the form of people’s homes and their identities and actions. This topic could be expanded to analyzing how such a relationship might occur. Such an evaluation may also be done in relationship to the categories and hierarchy of categories that I have provided[9].

Bibliography

Arijit Sen and Lisa Silverman. “Embodied Placemaking: An Important Category of Critical Analysis” Introduction. Making Place: Space and Embodiment in the City. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014).

Interviews conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

James Spradley, P. and David McCurdy, W.. The Cultural Experience: Ethnography in Complex Society. Science Research Associates, 1972), 83. (Outline).

Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991).

[1] Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991), 290.

[2] Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991), 288.

[3] My data was influenced by which students had conducted the interviews with the informants. Each group of Field School students that conducted interviews had a different format of asking questions and different types of questions. Some groups asked questions that were very relevant to home and its features, whereas others focused more on biographical information, which was irrelevant for my research. These discrepancies caused some informants to provide a lot more relevant information than others, and the result was varying amounts of data available from each informant. This issue could be resolved if all of the interviews were conducted by the same people. This would also make the data and conclusions drawn from the interviews more viable and consistent.

[4] Interview with Angela Pruitt conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[5] Interview with Charmion Herron conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[6] Interview with Lanard Robinson, Leroy Washington, and Mark Whaley conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[7] Interview with Pastor Wang Chao Lee conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[8] Arijit Sen and Lisa Silverman. “Embodied Placemaking: An Important Category of Critical Analysis” Introduction. Making Place: Space and Embodiment in the City. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 10.

[9] Reference Fig. 2.

Home is a number of things, and it takes on a different range of meanings with each individual. Mary Douglas says that home “is the realization of ideas” [1]. She also claims that home can either enrich the personality, or cripple and stifle it [2]. To each person, home has a different definition that can be analyzed in the context of the dwelling of the individual. A house is a type of space, but a home is a place, which is much more complex. Most often, the home is a domain of private space for the resident, and some boundary exists dividing the private space of the resident from the outer or public space. The outer world or domain is where social interactions with outsiders is made, whereas the inner domain is more intimate. All people have some type of such boundary. My analysis will focus on the construction of divides between the “inner world” of the resident and the “outer world” of the public. I will also discuss what home means to several residents of the Washington Park Neighborhood in Milwaukee through the use of ethnographic techniques.

When speaking of such domains and boundaries, a general understanding of culture is necessary. Culture is a complex idea that is not capable of being physically grasped. However, through primary sources such as oral histories, it is possible to understand the complexities of a specific culture. Some of the essential concepts are beliefs, expectations, social norms, and environment. Beliefs can refer to everything from religion to science and in between. Expectations and social norms can be interchangeable terms. They are the set rules that are established over a long period of time and are shaped by both beliefs and environment. Environment both encloses and shapes the other aspects of culture in terms of movement and procedure.

A cultural scene, like the one I have analyzed, is a physical area with some type of boundary that separates it from the surrounding environment or culture. Such a boundary can be a geographic feature like a body of water, or a man-made feature. A cultural scene will almost always possess cultural traits that vary from the cultural scenes around it. In order to understand culture, ethnographic techniques may be used. Ethnography directly relates to culture, as it is the dissection and analysis of it. Whether it be that of a high school bathroom or a library book club, conclusions can be drawn about the what, how, and why of that culture by using ethnographic analysis. I will begin by covering the Field Work Methodology that I utilized. I will then cover the social and physical characteristics of the Washington Park neighborhood. I will finish by analyzing the divide between the inner and outer worlds that many of the informants refer to as well as the culture of “home” in the context of the oral histories conducted by the BLC Field School.

Field Work Methods

The specific cultural scene of Washington Park was chosen by Professor Arijit Sen and the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School because of its unique economic and social conditions, which will be discussed later. Contact with the 22 informants was made through Arijit Sen and the BLC Field School and connections with the staff of ACTS Housing, who gave the Field School access to their clients and some staff. ACTS Housing is an organization rooted in the Washington Park neighborhood whose goal is to improve the social and physical aspects of the community through providing opportunities for homeownership. The organization also gave the Field School access to foreclosed homes that were going to be cleared by the city. Most of the informants are affiliated with ACTS, however some of them are tenants. Two of the interviews that I analyzed and will be discussing later were with tenants. Contact was made with these individuals through their landlord. An issue that we faced was that tenants were very underrepresented in our research. For this reason, the Field School could not make any generalizations about how tenants view home. This is significant because tenants perceive home differently than homeowners (i.e. differences in investment). However, their homes still hold meaning.

Of the 7 interviews that I analyzed, the informants’ ethnicities were African American and Hmong. All of the informants have faced substantial conflict in their lives, everything from immigrating from Thailand to being diagnosed with cancer. However, they were all very proud of their homes and how they have overcome these struggles. I was not involved in this process of informant selection, but began the semantic analysis afterwards. I was also not involved in the interview process. The interviews with the informants were conducted by 12 members of the BLC Field School[3]. This task was completed before I arrived, and I inherited the information for the purpose of my research.

My initial research was focused on the idea of home and what it meant to the informants. I began by listening to most of the 22 interviews that were conducted by the BLC Field School (more than the 7 I settled on). I took notes on which words the informants used most often to describe home. This step helped me to become more familiar with the taxonomy process and know what terms to look for. With the help of my professor, Arijit Sen, I narrowed the selection of interviews down to 7 that seemed to represent the Washington Park neighborhood the best. I then listened to these 7 interviews again and made rough, very specific taxonomies as I went. Once the rough taxonomies were made, I constructed digital, more narrow taxonomies using the rough copies I had made. With these digital copies, I was able to more clearly observe the similarities between the categories informants used. At this point, I could then identify the most common terms and create an overall taxonomy.

Once this research was completed, I began looking into the boundaries that residents create between their inner/private space and the outer areas in which socializing may occur. For this portion, I focused on the information provided by 4 of the 7 interviews that I had previously focused on. This boundary varies with each informant, but are always physical features that somehow divide or designate different types of space. The range of such a boundary may be contained completely in the structure of the home or extend to the exterior of the home and the community. The interests and social statuses of the informants that I focused on define where the boundaries are placed.

The Setting

The physical setting of Washington Park is western and northwestern Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Brookfield and Wauwatosa border this area to the west. The area is mainly residential, yet some establishments such as churches, restaurants, stores, and gas stations are present. The racial profile of the town is largely African American. There is also a large number of Hmong immigrants from Thailand that distinguish Washington Park from the rest of Milwaukee. Foreclosure, low homeownership, crime, and low income are prevalent issues in the area. My analysis will focus on the construction of divides between the “inner world” of the resident and the “outer world” where public engagement occurs. These two worlds will constitute as the major domains of the informants’ cultural scenes.

The Cultural Description

The domains I will be evaluating are inner and outer spaces distinguished by resident-constructed boundaries. I will later analyze the definition of “home” in general in the Washington Park Neighborhood. These ideas go hand in hand because of the nature of a home, for either public or private use or both. I will focus on the inner and outer domains in the context of 5 oral histories and 4 types of boundaries. These 5 informants reference the boundaries between the two domains most frequently out of the interviews that I analyzed.

Angela Pruitt: Angela Pruitt places her divide between her inner world and outer world at the outer walls of her house. The interior of her house is her own domain where she can do personal business or activities. However, she spends the majority of her time outside. Her yard, garden, and the rest of the neighborhood are her outer world. While her yard and garden are her property, she views them as community space that should be used for resource. During the interview, Pruitt mentions playing all day as a child, and then grabbing fruit and vegetables from neighbors’ yards when she got hungry. This is what she wants for the community.

Pruitt’s vision for the community is for there to be space where people can come together to communicate and strengthen relationships in the neighborhood. This goal corresponds with her desire for there to be as much space for interaction as possible, including her own property. She wants people to use the garden in her yard and the growing orchard across the street for their own benefit as long as they are respectful: “This is an orchard, we’re trying to grow fruit for the community. If we knock them [trees] down before they start to grow we won’t have anything.” Pruitt’s use of we and community in this statement show that her work is for others, not just herself.[4]

Charmion Herron: Charmion Herron places her boundary at the border of her property and lawn. Since her mother died, her home has become a sort of memorial to her mother’s memory. She makes sure to keep and preserve all of the features and items of the house just as her mother would have wanted it. Some of these features are outside the walls of the home. Herron refers to the home’s staircase often because her mother loved it: “My favorite [place] though I will say are the stairs… I know she loved the stairs.” For this reason, the staircase is her favorite feature of the home. However, she also mentions outdoor features such as her mother’s rosebush and geese planters in connection to the staircase: “The rose bush, she loved her rose bush. I have the geese outside the front porch that I keep… They all broken up and torn up but I keep ‘em because she for some reason every house she wanted her geese.” This suggests that Herron’s private, inner world also consists of the exterior of her home because of the connection she has created between the home and her mother’s memory. For Herron, her home is a type of safe haven. Her outer domain consists of everything outside her yard. She often refers to the block positively because of the memories she has growing up there and playing outside. She feels more safe on her block than in the rest of the neighborhood. Herron mentions crime in the neighborhood, for example at the McDonald’s nearby, but never refers to engagement in the community in the outer domain.[5]

Lanard Robinson and Leroy Washington: Lanard Robinson and Leroy Washington differ from the other informants being evaluated because they are tenants. They also live together in a home with one other friend and their families. The boundary they have created to divide their inner and outer worlds is the exterior walls of their building. Their home is where socialization and interaction with close friends and family occurs. During the interview, they often refer to the home as a family. They refer to the building as a safe place where their kids can play and where they can socialize with each other. Washington says during the interview, “I’ve made some friends… new family here. I’ve got three extra brothers… This my family, my friends… That’s what makes it home for me.” Robinson goes on to mention, “It’s one big family the whole building. My kids go up and down [the stairs]… they feel free to go over here…. It’s almost like a family.” The outer domain, on the other hand, consists mainly of places to eat, the park, and convenience stores:

Robinson: We have a lot of fast food restaurants around here… this neighborhood itself… my oldest [child]… grew up back in Milwaukee here... This neighborhood reminds me of all my kids when they were little, taking them to the park and having picnics. Now I’m doing the same thing 20 years later with my grandkids.” Interaction with people beyond their inner circle is rare, but when it does occur it is at these designated areas. Outside social interaction isn’t common for Robinson in Washington at other places in the community.[6]

Pastor Wang Chao Lee: The layout that Pastor Wang Chao Lee has chosen for his home reflects his position in the church and community, as he requires both public and private space. The open lower level serves as a public space, and the upper level serves as private space. The L-shaped staircase which is parallel to the front door serves as a barricade between the two aspects of his life. For example, his outer domain, the lower level, may be used for church meetings or consultations, whereas the inner domain, the upper level is solely for family use. His upper level is closed off, physically and hypothetically, to the public. It is a space that Lee and his family can use for more intimate interactions amongst the family. Lee does not refer to the outside of his home besides the church. This connection between the physical church and church meetings, which sometimes occur on his lower level, suggest that he considers the lower level of his home to be part of the “outer” domain. During his interview, Lee references how he intentionally created this divide: “The staircase… [is a] major redesign to my taste… And downstairs with more guests coming next to the kitchen… we want to host more guests…”, “ Larger bathroom, with kids… and the upper 3 bedrooms… knowing that the family will use it [bathroom] more.” This is a major example of how Lee has divided his home into the two domains.[7]

I found that the terms house, neighborhood, and people were used in every oral history in reference to home. Different people experience the same place in different ways due to varying contexts[8], and while the experiences and interpretations of the people were different, these common terms were always present. Common terms in reference to the physical structure of a house included cosmetic features, both indoor and outdoor. For example, kitchen, dining room, floors, paint, open concept, and yard were frequently mentioned. In reference to neighborhood, terms such as safety, crime, park, and change were common. When speaking of people, family, friends, and neighbors were also recurrent terms. All of these terms can be put into context depending on the informant.

Conclusion

The divide between private, non-social space and social space is an important aspect of home and community. All people need a place for public social interaction, but also a place to have to only themselves. Without this divide, there would be no rationality or expectations of how to behave in certain spaces. While this boundary is different for each person, the types of activities that occur in each domain have commonalities. Inner or private spaces, I found, are most often where people spend time with their families and close friends. Most often a more closed off and quiet space, it may be used for intimate conversations and interactions or time for one’s self. Outer space, however, is where interaction and engagement with acquaintances and the community is expected to occur. This may be in individual, defined places in the neighborhood or a more general area consisting of everything outside of the house or yard.

From the information provided by the informants, I can interpret that the Washington Park neighborhood has faced much social turmoil in the past, but is now improving through the work of many dedicated residents of the community. Many of the residents are concerned about crime and foreclosure in their neighborhood. They are optimistic, however, about the resources that are being put in place in order to minimize and potentially eliminate these issues. The focus of the residents is primarily on relationships with friends, family, and neighbors. Most believe that this bond is what will help lift the neighborhood out of its decades-long slump. Residents enjoy events like block parties, family get-togethers, and going to the park, after which the neighborhood is rightfully named. The park is certainly the centerpiece of the cultural scene.

Future research can be done evaluating the meaning of home in the context of the space and how it influences how residents act, think, and participate in daily activities. Everything from the structure of a building, interior and exterior, to its ambiance can impact how we think. For example, the factors of our physical environment may influence how we behave, how we understand others, and how we create who we are. The Spacial Performance theory states that we, as humans, create places, but those places make and shape us. With this knowledge, it would be interesting to assess if there is a correlation between the form of people’s homes and their identities and actions. This topic could be expanded to analyzing how such a relationship might occur. Such an evaluation may also be done in relationship to the categories and hierarchy of categories that I have provided[9].

Bibliography

Arijit Sen and Lisa Silverman. “Embodied Placemaking: An Important Category of Critical Analysis” Introduction. Making Place: Space and Embodiment in the City. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014).

Interviews conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

James Spradley, P. and David McCurdy, W.. The Cultural Experience: Ethnography in Complex Society. Science Research Associates, 1972), 83. (Outline).

Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991).

[1] Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991), 290.

[2] Mary Douglas. "The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space - PhilPapers." Social Research. 1st ed. Vol. 58. (New School for Social Research, 1991), 288.

[3] My data was influenced by which students had conducted the interviews with the informants. Each group of Field School students that conducted interviews had a different format of asking questions and different types of questions. Some groups asked questions that were very relevant to home and its features, whereas others focused more on biographical information, which was irrelevant for my research. These discrepancies caused some informants to provide a lot more relevant information than others, and the result was varying amounts of data available from each informant. This issue could be resolved if all of the interviews were conducted by the same people. This would also make the data and conclusions drawn from the interviews more viable and consistent.

[4] Interview with Angela Pruitt conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[5] Interview with Charmion Herron conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[6] Interview with Lanard Robinson, Leroy Washington, and Mark Whaley conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[7] Interview with Pastor Wang Chao Lee conducted by The BLC Field School 2016.

[8] Arijit Sen and Lisa Silverman. “Embodied Placemaking: An Important Category of Critical Analysis” Introduction. Making Place: Space and Embodiment in the City. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 10.

[9] Reference Fig. 2.